Some things I learnt from Dennis Sullivan

This post is to celebrate the Abel prize awarded to Dennis Sullivan. Sullivan is not only one of the deepest and broadest mathematicians, but also one of the most inspiring – in particular to me. I learnt much from him during my three years at Stony Brook and during his two visits to India. This is a somewhat whimsical account of some of this, with quotes from memory (hence error prone). Some stuff is general and some more technical.

Since much of this is about the process of mathematics it should also be useful for automated theorem proving – my excuse for posting this here 😃.

“Why be clever when we can be intelligent?”

A clever proof shows something is true, while an intelligent proof gives an understanding of why it is true and shows it is as a consequence. Sullivan was not saying do not be clever, just what is better if both are possible.

“Give a description on a single sheet of paper”

I had proved a result that gave a triangulation, i.e., a finite description of some spaces (homotopy compactifications of moduli spaces of punctured surfaces). Sullivan was very encouraging after a lecture on this, but asked for a description of the solution (not including the proof) that fit on two sides of a sheet of paper. Writing such a description, with the rest of the paper proving this, not only made the stuff much better written, but also increased my understanding of my work.

“Try to prove things without hypothesis”

This was in the context of a major question in mathematics called the Geometrization conjecture about $3$-dimensional manifolds. Sullivan described an approach he had tried which was to prove that all $3$-dimensional manifolds have conformally flat structures, and to deduce geometrization as a consequence. The actual statement of geometrization involves hypothesis on the manifolds implying that they had appropriate geometric structures. Sullivan’s point was that when we have such hypothesis (and the statement is false without them) we have to use them somehow, and using hypothesis can be hard.

In this case, the approach did not go far as it was not true that all $3$-dimensional manifolds had conformally flat structures. So we can try to get rid of hypotheses by making auxiliary statements, but these better be true.

Indeed in the case of geometrization a major technical advantage of the approach that Perelman carried out successfully was that the hypothesis of being aspherical was not needed – a statement was proved without this which could then be specialized.

“The power of calculations”

Sullivan exclaimed this during a mathematical discussion when my friend (and colleague) Harish showed why something is true with a calculation. Harish was quite amused that this exclamation was prompted by a simple calculation.

Moral: sometimes one just proves things by calculating.

Too much technique, too few interesting questions

Sullivan commented that mathematics has a problem of too much technique used for questions that are not that interesting. I am often struck by this after seminars where a lot of technical work gives a bounds on, for example, the slice-genus of a handful of knots.

One may conclude from this that one should seek more questions and focus less on technique. Perhaps we should collectively do this. However, at an individual level, unless one is at the very top, my experience is that mathematicians should accept that this is the nature of the beast and focus on technique. Or move on to something that is not really mathematics.

Trees, random walks, harmonic functions

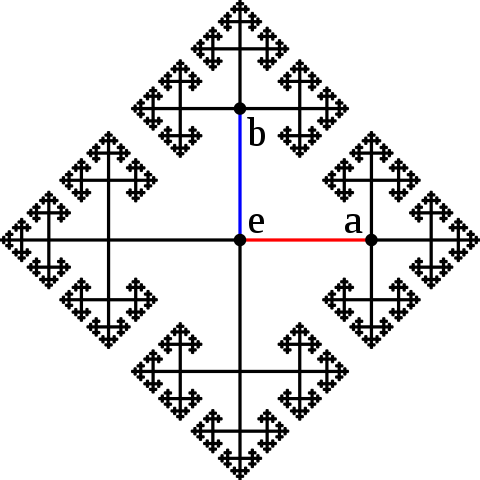

Suppose one wanders randomly in a tree such as the following.

There are more ways to go away from the center than towards it. Many results of Sullivan (to quote him) were built on just this. Specifically this gives a way of constructing harmonic functions on negatively curved spaces.

There are more ways to go away from the center than towards it. Many results of Sullivan (to quote him) were built on just this. Specifically this gives a way of constructing harmonic functions on negatively curved spaces.

Closely related is a favourite of Sullivan – the Riemann mapping theorem. In particular, if we have a surface with some boundary components at the bottom (inputs) and some on top (outputs) then (given a conformal structure) we have a (unique) harmonic map which is $0$ at the bottom and $1$ at the top. From this we get a locally flat metric, and hence a parametrization of conformal structures.

Magic of minimal models

This is Sullivan’s famous work, which I saw in a lecture in his course. It is magical how some formal algerbraic structures give homotopy groups, all captured by the simple equation $d\circ d = 0$.

$\infty$-structures

Probably the most important bit of mathematics that I learnt from Sullivan, especially as it reappeared in my mathematical life with Voevodsky’s discovery of Homotopy Type theory.

The basic idea is that in topology (and other mathematics) we often make choices, especially of perturbations (or of parametrizations). The result does not depend on these choices up to equivalence, and one traditionally works with this. However we can do better and consider the equivalence as an object. This may need another perturbation, but resulting equivalences are still equivalent. One can go on in this way to get an $\infty$-structure.

A specific case occurs when we discretize or (closely related to this) subdivide. The main idea is that many natural partial differential equations can be expressed in terms of the exterior derivative $d$ and the wedge product. These have discrete counterparts, and one can map to the discretization by averaging. One can similarly average when subdividing a discrete system to get a better approximation.

This works well for linear PDEs as the averaging maps $d$ to its discrete counterparts. However the wedge is not mapped to its discrete counterparts, and even worse the discrete counterparts of the wedge are not associative. However, if the wedge product is viewed as a degenerate case of an $\infty$-structure, then we do have algebraic structures and these map correctly. Sullivan has an approach to the Navier-Stokes equations which is based on this.

String topology and the Goldman bracket

The other candidate for the most important mathematics I learnt from Sullivan. Loop spaces have been central to topology for a while, and these are very useful new operations on them, inspired by the Goldman bracket.

Multiplying loops by taking one followed by the other is an old idea in topology – Poincaré’s definition of the fundamental group was based on these. In string topology multiplying loops is used to give an operation on families of loops (technically the homology of the loop space). This is done by perturbing, and then multiplying loops where they intersect.

Foliation cycles

This is Sullivan’s work, but I mainly learnt it from his paper and various people (in particular Slava Matveyev) and sources (Candel and Conlon’s superb book on foliations). A whole bunch of geometric results follow from one central idea – one such characterizes taut foliatations (a topological idea, the best work on which was due to my advisor David Gabai) as foliations all of whose leaves are area minimizing. The idea is roughly that when we are seeking structures in a cone, either such a structure exists or there is a dual structure obstructing it by having zero integral on subspaces that define the cone.

(Merely) Complex structures – somewhere where we know nothing

A famous question in mathematics is whether the $6$-sphere has a complex structure (more precisely a so called integrable complex structure). Complex structures are stronger than so called almost complex structures – about which we know essentially everything, and Kähler structures, about which we know a lot and do not know a lot. What I learnt from Sullivan is that, except in dimension $6$, we know nothing about complex structures other than what is true about almost complex ones. So we have examples of Complex but not Kähler manifolds – we construct these showing they are complex, and what we know about Kähler manifolds shows that these are not Kähler. But we have no way of ruling out having a Complex structure unless we can rule out almost complex structures.

The more general point – we can have whole classes of structures which are clearly interesting but about which we know nothing.

Lipschitz functions for topology

Traditionally in topology one either studies smooth objects or objects up to continuous functions. As I learnt from Sullivan, often the correct view is to consider Lipschitz functions and associated structures. A theorem of Sullivan says that in high dimensions these are unique. Yet Lipschitz charts give us much more structure than just continuous charts.

Measures in different contexts

Since I first saw this as an undergraduate, a general question that intrigued me was why countable additivity was the correct notion for a measure. Another thing I learnt from Sullivan – it is simply not true that countable additivity is always the correct notion – in some cases (e.g. amenability) something else like finite additivity is the correct notion.

“Quantum cohomology is just the equivariant cohomology of the loop space”

Here I am quoting Alexander Givental, speaking at a (7 hour long) Sullivan seminar. I cannot say I truly understand this. But a natural question is: the loop space does not need a symplectic structure but quantum cohomology does – why? The answer (from Sullivan) is that the symplectic structure gives a notion of positivity, which makes various sums finite.

“What is the central mathematical question in your life?”

Perhaps a good note on which to end, and leave the reader to answer this question I have heard Sullivan ask (with mathematical appropriately substituted).